Why Good Ideas Fail in the Real World

Jan 31

·

Reading time: 11 minutes

Article at a Glance

- Behavior only happens when motivation, ability, context, and social signals align at the same moment.

- Good ideas fail in the real world when one or more of those conditions is missing.

- A MAPS perspective shifts the focus from doing more of the same to understanding what is actually preventing behavior, and designing solutions that address the constraints.

Introduction

After more than a decade working in behavioral science and behavior change, certain patterns stop surprising you.A product launches with strong user testing behind it, but people don’t use it. A new internal tool is introduced, widely supported in meetings, and then employees avoid it in practice. A policy is rolled out after careful planning, only to generate a parallel system of workarounds almost immediately.

I’ve seen this play out across sectors and contexts that have little in common on the surface — from healthcare and public policy to financial decision-making, organizational change, and technology adoption. Time and again, the story is the same: a solid idea, grounded in market research, thoughtfully designed, carefully launched, and still far less effective in the real world than expected.

What becomes clear, after watching this pattern repeat, is that the ideas themselves are rarely the problem. In most cases, the strategy holds, the evidence is sound, and a lot of work went into execution. After all, people don’t set out to launch initiatives they believe will fail.

So where do things go wrong?

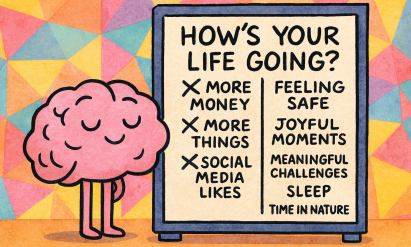

The breakdown happens at the level of understanding how human behavior actually works. We expect awareness to turn into action and initial motivation to translate into long-term engagement. In reality, however, consistent behavior change requires far more than knowledge or intent. It depends on many other factors — including attention, energy, timing, context, and social signals — all interacting at once.

For any behavior to happen, several conditions need to come together in the same moment. The good news is that this is not random, and we know what these four pillars of behavior are, how to diagnose, address, and work with them.

MAPS: Four Conditions That Must Align for Behavior to Occur

I've developed MAPS as a practical way of thinking about human behavior. It is grounded in established behavioral science research — including Susan Michie’s Behaviour Change Wheel — but refined through more than a decade of applied work in organizations and real-world decision-making to make it usable in everyday business contexts, not only in policymaking.

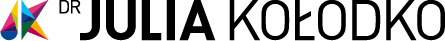

For a behavior to happen, multiple conditions have to be in place at the same time:

When even one of these conditions is missing, behavior won’t reliably occur. People may understand and agree, but their intentions won't translate into action — they’ll disengage over time or never start.

- People need to want to do the thing.

- They need to be able to do it.

- The environment needs to support the action rather than obstruct it.

- The social context needs to make the behavior feel acceptable, safe and desired.

When even one of these conditions is missing, behavior won’t reliably occur. People may understand and agree, but their intentions won't translate into action — they’ll disengage over time or never start.

MAPS stands for:

- Motivation, which describes whether something feels worth doing in that specific moment, not just in principle or in theory.

- Ability, which captures whether people have the cognitive, emotional, and practical capacity to follow through, given everything else competing for their attention and energy.

- Physical Context, which refers to the environment in which the behavior takes place, including processes, tools, timing, access, resources, and friction.

- Social Context, which reflects the influence of social norms, expectations, trust, and belonging.

Where Well-Intended Initiatives Tend to Break

Once you start looking at the world through the lens of MAPS, a pattern emerges. You'll notice that most ideas that look good on paper break in specific places, and in predictable ways.

- High motivation doesn't compensate for lack of ability.

- A supportive environment doesn't help if social signals push in the opposite direction.

- People may love a product concept or an organizational initiative but won't ever actually use it because of the many small inconveniences they'd have to face to get started.

What matters is not that all four of these pillars — Motivation, Ability, Social Context and Physical Context — are present in general, but that they align at the moment of action. Behavior change requires convergence.

Internal Factors

Two of these breaking points sit within the individual. They relate to how people experience the behavior itself, and whether they realistically have the capacity to follow through. These internal factors are often discussed in business practice, but rarely examined in full.1. Motivation: Overestimating Intention

One of the most common misconceptions about behavior change efforts is that intention leads to action. We assume that if people say something is valuable, they will want to do it. In reality, intention tells us little about the actual likelihood of using a product or engaging in an initiative. In fact, a large meta-review study showed that, on average, intentions explain only about 28% of the variance in future behavior.

For organizations, this matters because most products or initiatives are designed and evaluated at the level of intention: awareness, agreement, positive attitudes, stated commitment. When those indicators look good, we expect behavior to follow. When it doesn’t, we’re surprised. This is why intention-based metrics are so misleading.

Example: A wellbeing initiative is widely endorsed across an organization, yet participation remains low. This is because actively joining the program signals vulnerability, or an admission of “not coping well enough,” which makes many people reluctant to take part. The right intention is there, but emotions override the otherwise good choice.

2. Ability: Designing for Cognitive Capacity That Does Not Exist

Many initiatives assume a level of cognitive capacity that people simply do not have in everyday life. Products, services, and communications rely on people having the attention to notice prompts, the memory to recall what to do, the energy to make decisions, and the self-control to follow through repeatedly.

Example: A health app designed to help people build healthier habits is grounded in good science and thoughtful design. But getting started requires downloading the app, creating an account, and completing long onboarding surveys. Then, users have to remember to open the app daily and log data. The mental effort of remembering, deciding, and tracking outweighs the perceived benefits.

External Factors

Beyond motivation and ability, two external conditions also need to be in place for behavior to change: the physical environment and social context.These are the factors most often overlooked in practice. I see this repeatedly in my advisory work. Managers often consider motivation and ability, but overlook the external context in which behavior happens, even though those conditions matter just as much.

3. Physical Context: Friction, Friction, Friction

Physical context shapes behavior more than most strategies acknowledge. Systems, processes, timing, access, and even the tiniest of frictions all determine whether an action will fit naturally into daily routines or become an ongoing source of effort.

Example: A policy encourages a desirable behavior but requires navigating forms, approvals, or poorly aligned timing. Compliance remains low and informal workarounds emerge. The situation is framed as a mindset problem, even though it is the process design that pushes people back to their old paths.

4. Social Context: Treating Behavior as an Individual Choice

Many initiatives are designed as if behavior were a private, individual decision. In reality, people constantly scan their environment for social cues. They notice what leaders actually do, not what they say. They pay attention to what feels normal, rewarded, or risky within their group.

Example: An AI education program is praised by leadership in presentations and emails, but leaders continue working in the old way, implicitly signaling that output and availability should always take priority over learning. Employees adjust their behavior accordingly.

A Better Way: From Doing More to Understanding What’s Broken

Seen through the lens of MAPS, the typical response to failure starts to look predictable. When initiatives struggle, the most intuitive response is to do more of what has already been done. We educate more. We re-explain. We launch another campaign, refresh the messaging, add guidance, reminders, training, or incentives. The underlying assumption is straightforward: if people are not acting, they must not understand well enough yet.

Any of these responses can help in some situations. But each of them targets only a narrow part of what drives behavior, and only under specific conditions. When they don’t work, repeating or amplifying them rarely changes the outcome. More often, the barrier sits elsewhere and requires a different response.

A more effective approach is to pause before designing another initiative or change, and ask a different question: where is behavior actually breaking?

Most organizations already have enough insight. What they lack is a way to integrate it into how behavior actually unfolds in practice. This is where MAPS becomes useful.

The MAPS approach helps locate the behavioral root cause before jumping to solutions. Once you understand whether the constraint sits in motivation, ability, physical context, or social context, you can design responses that address the real limitation, rather than repeating the same approach in louder or more elaborate forms.

Using MAPS in Practice

MAPS is useful both before launch and after. It helps reveal blind spots in new ideas and explain why existing initiatives struggle in practice.

Using MAPS does not require a complex diagnostic process to be valuable. While a comprehensive analysis is often desirable, it is not always feasible under real-world business constraints, time pressure, or limited budgets. In those situations, you can make meaningful progress with a simpler shift: changing how you frame the problem and what you ask first.

The key is to deliberately consider all four conditions for behavior, rather than defaulting to the one that feels most obvious or easiest to address.

- When considering Motivation, ask whether the action feels worth doing in the moment it is required. What emotional, identity-related, or perceived costs might make people hesitate, despite agreeing with the goal in principle?

- When considering Ability, ask whether people realistically have the mental space to follow through. What does this ask them to remember, decide, or think about during an already full day?

- When considering Physical Context, ask how the environment shapes behavior. Where does friction appear? What makes the desired action harder than it needs to be?

- When considering Social Context, ask what people learn from others. What do leaders and groups model in practice? What feels normal, risky, or rewarded?

A Final Reflection: What Fails When We Misdiagnose Behavior

Up to this point, I’ve deliberately used practical business examples — products, internal tools, initiatives, policies. That’s where the gap between intention and behavior is easiest to observe. The same pattern, however, shows up well beyond organizational settings:

- We see it in public health and climate action, where awareness is high yet follow-through remains low.

- We see it in anxiety around AI and automation, where many people understand the arguments intellectually but feel caught between fear and paralysis. At the same time, organizations invest in AI education and upskilling, only to see people start trainings and quietly drop off as motivation fades and everyday pressures take over.

- We also see it in rising burnout and declining wellbeing, where well-intentioned initiatives are often designed in ways that make accessing support harder than it needs to be.

Across these and many other domains, people are navigating uncertainty, social pressure, identity threats, cognitive overload, and environments that reward short-term coping over longer-term change. Expecting better behavior without addressing those conditions sets both individuals and systems up for frustration, or even failure.

This is where the MAPS perspective becomes especially useful. It offers a way to make sense of why so many people struggle to change their behavior, even when they genuinely want to.

The full MAPS model goes deeper, outlining additional factors within each pillar and a more detailed set of diagnostic questions. For those who want to explore that level of depth, I’m happy to share more.