Rethinking Success: KPIs for a Life That Actually Feels Good

Sep 14

·

Reading time: 17 minutes

Article at a Glance:

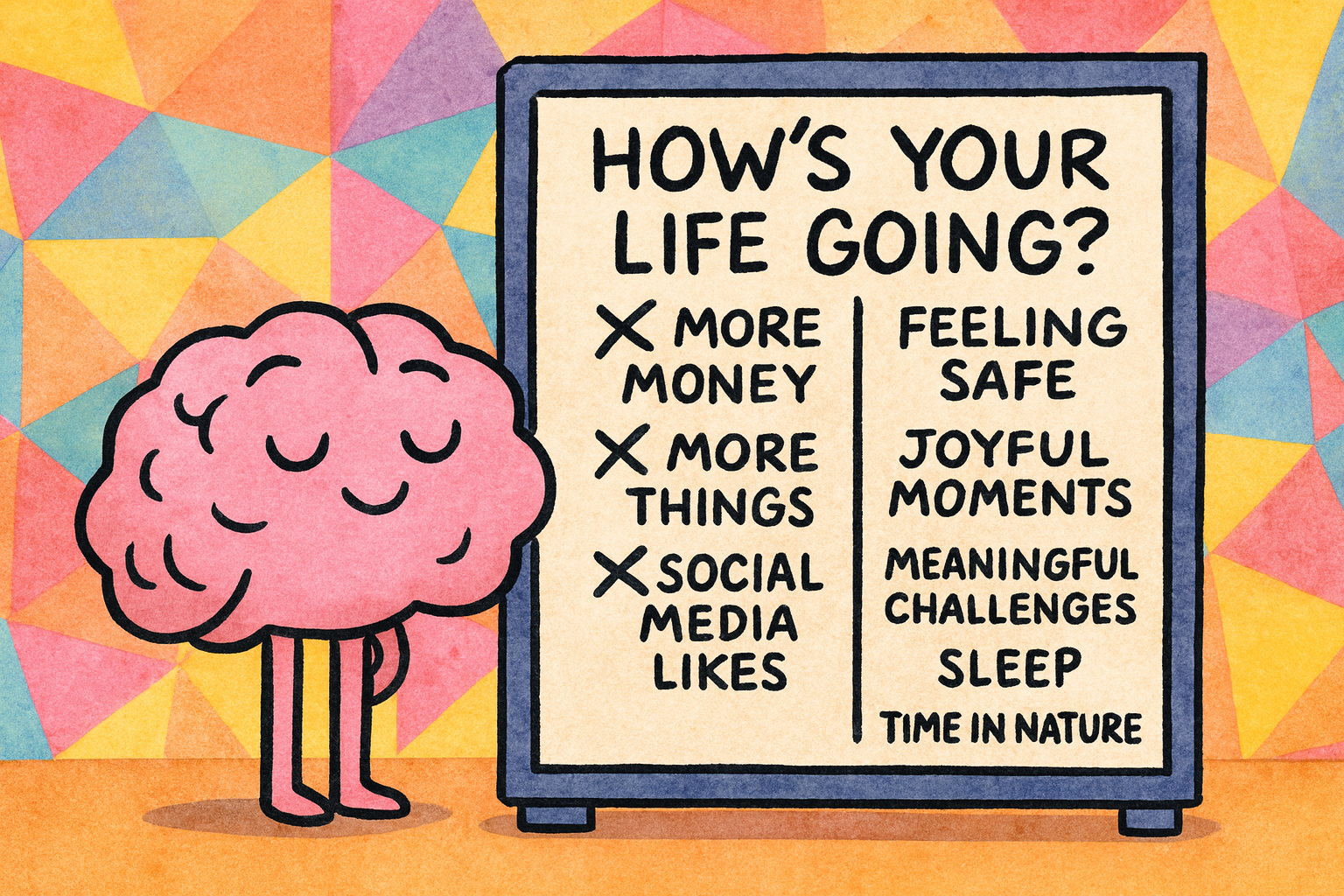

- We’ve been measuring the wrong things. Money, status, and busyness may signal success but they don’t make life feel good. Chasing these “external KPIs” leaves many people emotionally empty, even when life looks impressive on paper.

- Most companies and individuals track what’s visible, not what’s valuable, and end up optimizing for burnout.

- Psychology and neuroscience show that meaning, connection, nervous system calm, and aligned effort are better predictors of sustainable wellbeing.

- We confuse hedonic pleasure with real, lasting fulfillment.

- Eudaemonic wellbeing — grounded in purpose, growth, and contribution — is harder, but more rewarding.

- Even high performers fall apart when their internal signals are ignored, especially if they’re measuring success with the wrong yardstick.

- We need a new dashboard — one built on behavioral science, not hustle culture.

- The New KPIs for a Good Life include:

- Mental & Emotional Wellbeing: Inner calm, focus, boundaries, reflective time.

- Nervous System Regulation: Sleep, rest, nature, movement.

- Relational Depth: Time with people who “get” you, belly laughs, shared rituals.

- Meaning & Purpose: Aligned work, autonomy, awe, contribution.

- Everyday Groundedness: Unscheduled time, cozy rituals, feeling safe in your space.

Introduction

We’ve all been there. A decent job. A stable income. Maybe a few promotions, holidays under palm trees, a growing family, a new apartment or car or phone — all the things we once believed would make us happy and fulfilled. From the outside, it looks like everything’s going well. Friends say, “You’re doing amazing!” We nod, smile, say thank you — but inside, we feel off. Like something important is missing, even though we can’t quite name what. And we definitely know we shouldn’t be feeling this way. I mean, we have it all, right?

This feeling is certainly not unique. Over the last few years, I’ve found myself drawn to memoirs by people who reached the very top: Viola Davis, Matthew Perry, Britney Spears, and Jane Fonda, to name a few. They’re all wildly successful, yet they all share the same inner experience: burnout, disconnection, depression, emptiness.

So what’s going on here? Why do most of us, regardless of our circumstances, end up feeling like something is missing? It’s easy to assume this kind of discontent is a personal failure. That if we’re not feeling deeply satisfied, we must be doing something wrong. But what if the problem isn’t us but rather the metrics we’re using to define success in the first place?

Let’s dig in.

Part 1: Success Metrics That Mislead

Current metrics of personal success — money, status, busyness — aren’t just inadequate; they’re misleading us about what truly contributes to a good life.

1. The Illusion of Money and Status

It’s not that money doesn’t matter. It does, especially when you don’t have enough of it. Financial security provides real psychological safety: a roof over your head, food on the table, options in crisis, room to breathe. But once those basic needs are met, the relationship between income and happiness starts to shift.

A landmark 2010 study by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton showed that while life satisfaction rises steadily with income, emotional wellbeing — how happy, calm, or stressed people feel day-to-day — plateaus around $75,000 per year (in U.S. data from 2008–2009). That finding quickly became a cultural touchstone, suggesting there was a “happiness cap” on income.

But newer data challenged that assumption. In 2021, Matthew Killingsworth used real-time app-based data to measure moment-to-moment happiness and found that it continues to rise with income, even above that threshold — though at a slower rate. Then in 2023, Kahneman and Killingsworth collaborated to reconcile their findings. They concluded that for most people, happiness does increase with income. However, for those who are already deeply unhappy, the emotional benefits taper off earlier, at around $100,000.

In other words, more money can make you happier, but only to a point — and not equally for everyone. What matters most is financial security, not endlessly climbing the income ladder.

And money isn’t the only factor. Research across 166 countries showed that in the short term, economic growth (like rising GDP) can improve our collective wellbeing. But over time, social capital — trust in others, strong relationships, supportive communities, and fair institutions — is a stronger and more consistent predictor of wellbeing.

This echoes the Easterlin Paradox: while individuals with higher incomes tend to report greater life satisfaction, increases in a country’s average income over time don’t always lead to higher national happiness.

2. The Busyness Trap

If money is our most obvious marker of success, busyness is its invisible twin. We wear it like a badge of honor — a signal to the world that we’re needed, productive, important. Being busy has become a kind of moral currency: the fuller your calendar, the more worthy you are.

It’s no coincidence that we glorify being busy. Research by Silvia Bellezza and colleagues (2017) found that in modern Western culture, busyness is perceived as a sign of status. People who are always “on” — working late, skipping vacations, juggling endless meetings — are seen as more competent, ambitious, and important than those who aren’t constantly busy.

But beneath that surface lies a very different story. Chronic busyness acts like a socially sanctioned addiction. It gives us short bursts of reward — a sense of urgency, movement, even meaning — but over time, it chips away at the very things we need to thrive. The more we normalize overwhelm, the more we disconnect from our bodies, our relationships, and ourselves.

And yet we keep going. Because in many systems, especially high-performance workplaces, busyness is how we signal value.

Neuroscience shows that when we’re constantly in motion, our nervous system can get stuck in a low-level survival mode — a chronic state of activation that keeps us vigilant but drained. When this state becomes the norm, it wears down our ability to focus, connect, and bounce back.

Here’s what science tells us:

- Polyvagal Theory (Porges, 1995) explains how chronic stress traps the body in fight-or-flight or shutdown modes, making it harder to return to a sense of safety.

- Chronic stress research (Arnsten, 2009) reveals that prolonged overload impairs the prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain responsible for decision-making, creativity, and emotional regulation.

3. Misguided Corporate KPIs

It’s not just individuals who are measuring the wrong things. Organizations are doing it too, especially when it comes to wellbeing.

Most companies aren’t ignoring wellbeing. In fact, many are investing in programs, platforms, and internal initiatives meant to support it. But the challenge lies in how we measure success. Corporate KPIs are built to track what’s visible — participation rates, usage stats, hours logged — because those things are easy to quantify. But visibility doesn’t always equal impact. And just because something is measurable doesn’t mean it’s meaningful.

A company might know how many people attended a mindfulness session or downloaded a resilience toolkit — but not whether anyone feels calmer, more connected, or more able to handle the complexity of their job and life. We’re tracking compliance, not capacity. Visibility, not vitality.

That’s not a failure of intent. It’s a limitation of the system. Most organizations are trying to support wellbeing — but they’re doing so using the same tools, metrics, and mindsets designed for productivity. And that’s a mismatch.

The result? Employees are often asked to self-regulate in environments that remain chronically dysregulating. Stress is framed as a personal management issue rather than a collective or cultural one. And while the language has shifted, the pressure hasn’t.

Here’s the hard truth: you can’t spreadsheet your way to employee wellbeing. If your KPIs aren’t measuring whether people feel safe, energized, connected, rested, joyful — then you’re not measuring wellbeing. You’re measuring participation.

Part 2: What Actually Makes Life Feel Good (And What We Get Wrong)

So what happens when the way we measure success — as individuals and organizations — is misaligned with what truly makes life feel good? We end up busy but unfulfilled, productive and “successful” but burned out and devoid of meaning.

If money, status, and output aren’t the best indicators of a good life… what is?

Let’s look at what the science says about what actually makes life feel good — and why so many of us are missing it.

Disclaimer: The next section isn’t a thorough meta-review of every happiness study ever conducted. But there are a few core concepts from psychology and neuroscience that help explain why so many of us feel unfulfilled — even when we’re technically “doing well.” And why the life that actually feels good often looks different from the one we’re taught to chase.

1. We put “happiness” into one bucket and forget to distinguish — and seek — eudaemonic happiness, not just hedonic happiness.

One of the biggest blind spots in how we talk about happiness is that we don’t distinguish between two very different types of it.

- Hedonic happiness is what most of us are familiar with. It’s about pleasure, ease, enjoyment — the feeling you get from eating your favorite dessert, binge-watching a TV series after a long week, or booking a spontaneous weekend getaway. It’s the dopamine hit of life. Necessary, nourishing, and often fleeting.

- Eudaemonic happiness, on the other hand, is deeper. It’s the sense of meaning that comes from contributing to something bigger than yourself, growing through effort, or aligning your actions with your values. It doesn’t always feel good in the moment but it leaves you with a sense of wholeness and direction. It’s the satisfaction of finishing a project that stretched you, helping a friend through a hard time, or volunteering for a cause that reflects your values. It’s saying no to something that isn’t aligned, even when it’s popular or profitable. It’s writing, creating, or building something that expresses your deeper self.

The problem is that we’re conditioned — culturally, socially, economically — to chase the hedonic version. But it's eudaemonic happiness that is far more sustainable and predictive of long-term wellbeing. People who report higher levels of purpose, personal growth, and contribution also show lower rates of depression, greater resilience, and more fulfilling relationships over time.

Neuroscience helps explain why. Hedonic pleasure is largely driven by dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with reward, novelty, and immediate gratification (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2015). But eudaemonic experiences engage other systems — including oxytocin (Zak, 2005) for connection, serotonin for contentment (Young, 2007), and long-term changes in brain regions associated with meaning, empathy, and self-reflection (Huta & Ryan, 2010; van Reekum et al., 2007).

2. We chase happiness and forego meaning.

The distinction between hedonic and eudaemonic happiness has another layer. It’s not just about pleasure versus purpose but also about the difference between seeking happiness and seeking meaning. And that difference matters more than we think.

According to psychologist Roy Baumeister and colleagues (2013), a happy life is one where your needs and desires are met. It’s focused on feeling good in the moment — on ease, comfort, and enjoyment. A meaningful life, on the other hand, is about being part of something bigger than yourself. It often involves effort, sacrifice, and even discomfort, but it creates a lasting sense of coherence and direction.

The problem is that we’ve been taught to prioritize the former. We’re told to chase happiness through lifestyle upgrades, feel-good habits, and quick wins. Discomfort is something to avoid. If something isn’t effortless, on-demand, or wrapped in pastel wellness branding, we assume it must be bad for us. But over time, this pursuit of ease becomes a trap. It feels good in the moment but slowly leaves us feeling empty.

Baumeister’s research confirms this: people who report meaningful lives tend to experience more stress, effort, and complexity — but also greater life satisfaction and emotional resilience. Meaning doesn’t always feel good. But it builds something solid.

Because meaning lives where happiness often doesn’t:

- In the challenge that shapes you.

- In the work that stretches you.

- In the conversation you didn’t want to have — but had anyway.

- In the choice to act from values, not convenience.

So if your life looks full on paper but feels empty or flat, you’re not broken. You may just be chasing the wrong thing. If we want lives that feel rich, grounded, and alive, we need to stop asking, What would make me happy? and ask What would make this meaningful?

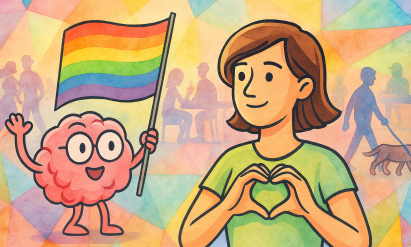

3. We’ve become socially isolated.

We’re wired for connection, but the structures of modern life increasingly pull us apart. We spend more time on screens than around tables, scrolling through updates without speaking to anyone who really knows us. And it’s costing us.

Research shows that time spent with close friends and community — what economists call “relational goods” — is one of the strongest predictors of wellbeing. Not casual socializing, not networking, but the kind of relationships where you feel safe, supported, and fully yourself.

Being surrounded by the right people isn’t luxury. It’s a psychological need. And yet, we tend to treat time with family and friends as a nice-to-have — something to fit in if the calendar allows.

If we want lives that actually feel good — not just for our lives to look good on paper — we need to design for connection. And we need to make sure our new KPIs for a Good Life include the things that actually make life feel meaningful — like time with close friends, shared meals, belly laughs, and having in our lives people we can count on.

4. Our lives have gotten too serious.

Somewhere along the way, we turned life into a performance review. Every hour must have a purpose. Every action must be productive. If it isn’t contributing to a goal, it’s a waste of time. And God forbid you take a day off to do nothing, and not feel guilty about it.

But here’s the truth: not everything has to be constructive. Some of the most essential elements of a good life — play, joy, awe — don’t tick any of these boxes. You just do them because they feel good.

And yet, they leave an imprint that goes deeper than we realize, and we’re starting to understand why. Research shows that “non-productive” experiences like play, joy, and awe don’t just make us feel good — they broaden our attention, build resilience, and deepen our sense of meaning. Play strengthens adaptability (Brown, 2009), joy helps us grow through openness (Fredrickson, 2001), and awe — even in small doses — reconnects us to something larger than ourselves (Keltner & Haidt, 2003).

5. We forget we have a body from the neck down.

To lead a good life, your nervous system needs to be in the right state.

It sounds obvious. But most of us don’t live that way. We treat wellbeing like a mindset problem — something to fix with affirmations or a better morning routine. But it’s our nervous system that runs the show, whether we acknowledge it or not.

When we’re regulated — when we feel safe, rested, and connected — we’re more resilient, creative, and socially attuned. When we’re not, even the best tools won’t land. You can’t enjoy life if your body thinks it’s under threat.

And here’s the flip: you can’t outperform your physiology. Your calendar might run on ambition, but your body runs on rhythm. If we want lives that actually feel good, we have to start listening to our bodies, not just our overachieving egos and bully minds.

Part 4: The New KPIs for a Good, Accomplished, and Meaningful Life

We’ve spent so long measuring success by external outputs — income, status, deliverables — that we’ve lost touch with the internal signals that tell us whether our life is actually working.

As a behavioral scientist — and as a human being with a nervous system and professional ambitions and goals — I’ve lived the gap between what we’re taught to pursue and what actually supports wellbeing. And I’ve come to believe we need better tools.

What follows is a new kind of dashboard: Key Progress Indicators for a Good Life. These are the metrics I propose we start paying attention to — personally, organizationally, and societally. They’re designed to help us build lives that feel fulfilling, not just look impressive on paper while quietly leading us toward burnout and emotional emptiness.

KPIs for a Good Life

These KPIs are not meant to be your new to-do list, and you definitely don’t need to track them all. Start with a few that resonate today. Ignore the rest. Come back to them later if something starts to feel off.

🧠 Mental & Emotional Wellbeing

- # of hours of inner calm per week (time feeling emotionally regulated, not rushing or spiraling)

- # of hours in deep focus per week (distraction-free time doing meaningful, mentally engaging work)

- # of decisions offloaded this week (tasks delegated, simplified, or automated to reduce mental load)

- # of satisfying mental challenges tackled and emotionally difficult things you did in a month

- # of boundaries set this month

🫁 Nervous System Regulation & Physical Wellbeing

- # of mornings you woke up rested this week

- # of hours spent in nature this week

- # of joyful or playful movement sessions (e.g., walks, stretches, dancing, playing games)

- # of hours of guilt-free rest (actual downtime, no screens, no productivity)

- # of times you intentionally downregulated stress (e.g., breathwork, naps, yoga)

💬 Relational Depth & Social Wellbeing

- # of hours spent with close friends or loved ones this week

- # of belly laughs shared

- # of acts of kindness or small surprises given

- # of people you can call in a moment of crisis or meaningful conversations where you felt seen, heard, or energized in a week

- # of collective experiences this quarter (e.g., concerts, rituals, game nights, shared awe)

🌱 Meaning, Purpose & Alignment

- # of hours spent this week on activities aligned with your values

- # of times you stopped in awe or tiny joys noticed this week

- # of hours spent doing something that matters to you, regardless of outcome

- # of times you looked forward to something with hope or excitement

- # of times this week you were able to act with autonomy (e.g., make a decision, follow an idea, or do something *your way*, without needing to ask for permission or compromise your values or vision)

🏡 Safety, Simplicity & Everyday Groundedness

- # of hours in unscheduled time this weekend free from guilt or obligation

- # of meals mindfully prepared or savored (no multitasking allowed)

- # of hours spent alone (and actually enjoyed)

- # of hours your space felt calm, clear, or quietly comforting

- # of small rituals that helped you feel grounded (e.g., tea, music, candles)

Conclusion

Ok, I know this list is long. But imagine if we — as individuals, teams, and even entire countries — measured progress based on these metrics. Not just money made or meetings attended, but joy felt, connection sustained, purpose lived, and nervous systems regulated.

We’re in the middle of a global crisis of meaning and mental health. It’s time we started treating the right things as the metrics that matter.

So here is your prompt for reflection and for reinvention: What would your life look like if you measured the right things? What if your calendar and your heart were finally aligned? And what might change — in your team, your company, your family — if we all started to design for lives that actually feel good?