Marketing vs. Behavioral Economics:10 Differences in Approach to Behavioral Change

Article at a glance

- Both marketing and behavioral economics have the same goal — to influence and change behaviors — yet these two disciplines approach this objective in different ways.

- There are ten key evidence-based insights that support behavioral approach to behavior change:

7. Context has a more significant impact on our behavior than who we are.

Yet the tools used in these two disciplines and the approach take on differs. Below is my list of the top ten differences explaining how the behavioral science approach to behavior change differs from marketing and what marketers can learn from behavioral scientists to more effectively design choices.

Observation #1: To know whether something works, you need to measure it

Context matters. Each day, each place, each person, and each advertising block on television is a different context. The fact that consumers like something at one moment in time doesn't mean they will like it in the next. I may prefer apples to oranges today but choose oranges over apples tomorrow.

This is why behavioral science pays so much attention to basing its conclusions and recommendations in evidence. All behavioral change tools and insights you hear me talk about here and that you read about in other places come from reliable research and are evidence-based. There is little room for assumptions, guessing or relying on the preferences of experts or managers, just because they like something (as is so often done in marketing).

Evidence-based approach means that we look at what people really do, not at what they say they want to or will do. People rarely know what they want or what the real motives behind their behaviors are. This is why the behavioral approach is based on experiments and well-planned observations, as only such studies can reliably verify whether a given intervention (communication, product, ...) is effective.

Observation #2: We're all the same

Marketers typically segment customers based on psychographic or demographic characteristics. They look for differences between people, identify those groups that match their brand and build strategy and communication around what distinguishes a target group from other groups.

Behavioral economics assumes that we are all the same. We all have limited mental resources and lack self-control. We all value what's “here and now” more than the future. We all use mental shortcuts, and we use the same mental shortcuts. This, in turn, causes us to be prone to cognitive biases. We follow the crowd and are susceptible to the influence of others, especially the people we like and admire or those who are similar to us.

Behavioral change interventions use these ubiquitous biases — rather than focusing on the uniqueness of different target groups — to influence behavior.

Observation #3: Our behavior is controlled by unconscious mechanisms, so there is no point in asking people about their motivations

Because we have limited mental resources, we often use cognitive biases when “making” decisions.

Imagine an iceberg floating in an ocean. You only see its tip, and while the visible part may seem big, it's actually just a small part of the entire iceberg. The same goes for our behavior: What we see (are aware of) is only a tiny part of the whole decision-making process.

Consequences? While we think we know better, in reality, we don't have access to the unconscious, “underwater” part of our minds. We think we know why we made a decision, but we really don't.

Moreover, research shows that the mere fact of justifying our decisions (e.g., explaining why we like a product) can change our attitudes towards the thing. This attitude change happens not only with regard to everyday, trivial things but also with regard to topics as important as our political views or our beliefs regarding controversial topics such as abortion. Behavioral research shows that we are so unaware of our choices that it is possible to change our opinion in a matter of minutes.

Observation #4: Our mind is flat and uses mental shortcuts

Our minds are incredibly complex machines, and our decision-making processes comprise multiple layers of consciousness and unconsciousness. On the other hand, however, they are flat and simple. We have limited perception, limited mental resources, and use mental shortcuts. Our minds lack the processing power necessary to analyze all the input that comes our way, so we need to use mental shortcuts to go about our everyday lives. The cognitive biases I write about so often and that behavioral scientists study are nothing more than a way for our “limited” minds to function in the complex world we live in. The behavioral approach uses these biases as behavior change tools rather than relying on people's declarations, their conscious motives, and using education and rational argumentation to influence behavior.

Observation #5: Our preferences often change and therefore declarations and intentions rarely translate into behavior

Did you know that the average correlation between intentions and actual behavior is 0.23? In simple terms, this means that less than a quarter of consumer declarations you hear in marketing research will translate into actual behavior. This is why, in behavioral economics, the focus is on behavior rather than on preferences, declarations, or intentions.

Observation #6: If you want to change a behavior, you only need to change behavior

Behavioral scientists have one goal: to change behavior. Not attitudes, not beliefs, not values but behaviors. Marketers, on the other hand, often focus on the former. There actually seems to be a belief among marketers that to change behavior, you first need to influence beliefs or attitudes, or even to change people's values. That's simply not the case.

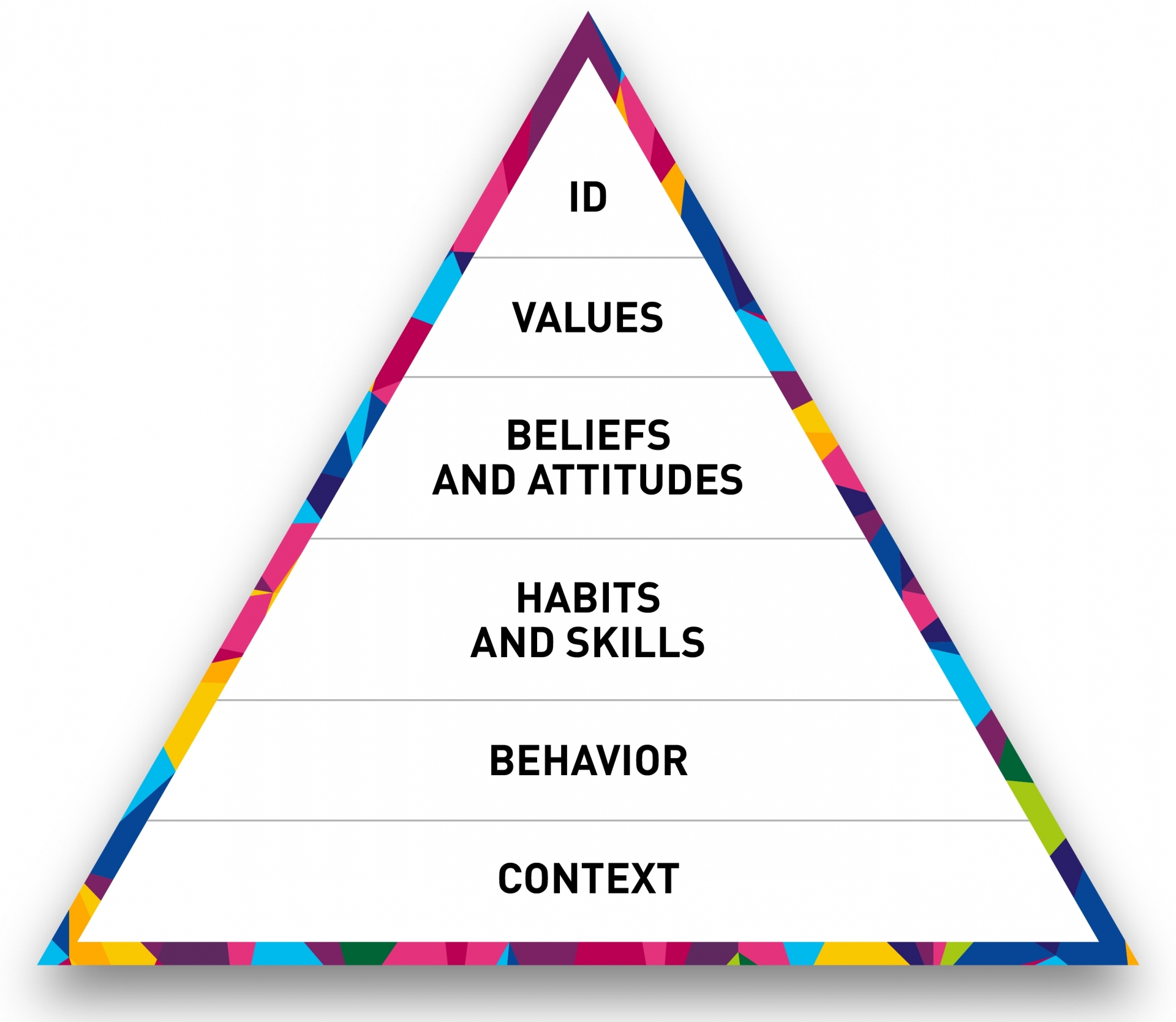

My favorite model that showcases the difference between these two approaches is the (slightly modified) Dilts Pyramid of neurological levels. According to Robert Dilts, any event can be explained on five levels, by answering the following questions:

- Context – Where? When? With whom?

- Behavior – What?

- Skills and habits – How?

- Beliefs, attitudes, and values – Why?

- Identity (ID) – Who? Who am I?

The objective we want to achieve is influencing the second level of the pyramid: a behavior. We want consumers to do something, for example, to buy a product or to use our service. We can approach this objective in two ways — going from the top of the pyramid down or going from the bottom of the pyramid up.

The bottom-up approach to behavior change

The most basic level we can influence is the context (environment) in which a person functions. This is what behavioral scientists call choice architecture – the re-designing of an environment to elicit the desired behavior. This level is the least personal level since it deals with what's outside of us, not our thoughts or emotions. This is also the bottom-up approach to behavior change as we are working with a lower level of the pyramid to influence a higher level of the pyramid (a behavior).

And we can keep going up the pyramid. Context affects behavior, which in turn affects skills or habits: what we do often can become a skill or a habit. We can continue going up the pyramid, reaching its higher levels: beliefs and attitudes, then values, finally reaching one's identity.

The top-down approach to behavior change

The whole process also works the other way around: from the top to the bottom of the pyramid, whereas our identity can influence our values, which in turn influence our beliefs, skills, and habits, which then influence what we do and the environment in which we spend time.

For example, the fact that I was a Ph.D. student (identity) influenced my values: Truth and searching for it became more and more important as I walked the academic path, compared with what I valued when I worked in marketing. This, in turn, translated into my belief that something is not real until it is scientifically proven. This belief affected my skills as I became an expert in designing experiments, and finally my behavior (spending countless hours gathering and analyzing data) and the environment in which I functioned (third floor at the Warwick Business School).

First, the lower the pyramid level, the easier it is to yield a change. This is because we operate at a more superficial level of a human being – we are less affected by the fact that someone changes the layout of how food is displayed in a cafeteria than by someone trying to influence our identity as a meat-eater, by referring to unethical aspects of eating other animals.

Secondly, there is no need to change a higher level of the pyramid to change a lower level (behavior). Despite the common assumption in marketing, we rarely really want or need to change people's attitudes or beliefs. What we really want is to change their behaviors. We want the consumer to buy, to use, to go, to eat, to subscribe.

So let’s learn to distinguish between lower and higher levels of the pyramid, stop confusing means with ends and focus on what we are really interested in, namely behavior change.

Observation #7: Context has a greater impact on our behavior than who we are

The fundamental attribution error — our tendency to ascribe one's behavior to their personality, while underestimating the impact of a situation — is one of the fundamental cognitive biases that hinders marketers' work. As behavioral science research shows, context is crucial and has a significant impact on behavior. This is why behavioral scientists place so much emphasis on the context in which decisions are made and less on who the audience is and how one target group differs from another.

Observation #8: Education doesn't lead to change

We all have two information processing systems, known as System 1 and System 2. System 1 is automatic, fast, and impulsive. System 2 is rational, analytical, and thinks about the long-term consequences of our actions.

For education to work, System 2 needs to be involved as it's System 2 that is responsible for understanding arguments, analyzing them, and deciding whether they are valid. The problem is that we rarely involve System 2 in everyday decisions. As Daniel Kahneman said: Thinking is to humans as swimming is to cats; they can do it, but they'd prefer not to.

This is why attempts to educate consumers typically look like this:

Observation #9: There are more effective ways of influencing behavior than communication

In marketing, it's all about communication. That's what the majority of marketing budgets and time is spent. Yet, communication too often requires the involvement of System 2: We need to encode and understand a message so that it can influence our behavior. Since consumers rarely engage System 2 in decision-making processes, and even less so when watching advertisements or reading leaflets, communication too often ends up being ineffective, especially when we consider how much time and money goes into producing it vs. the impact on behavior it has. This is why behavioral scientists aim to work with choice architecture and to use our cognitive biases as behavior change tools, rather than putting all eggs in the communication basket.

Observation #10: Perception is more important than reality

The truth doesn’t matter. All that matters is what people know and think about a particular subject.

Scientific research may show that eating the right types of fat is healthy and that a high fat (ketogenic) diet is an effective way to lose weight. Yet, none of this matters if someone believes that eating fat makes them fat. In the same way, if a diabetic patient believes that going on mealtime insulin will cause them to be hypoglycemic, they will not want to take the drug, even if data shows it'll be good for their health.