Us vs. Them: Why Our Society and the World Are Becoming Increasingly Divided

Article at a glance

- Evolution has shaped us in such a way that we see the world in terms of us vs. them and have the tendency to discriminate those who do not belong to our group.

- Social identity theory explains how this process of dividing ourselves into us vs. them happens.

- Several cognitive biases explain this tendency.

There is one day a year in Poland when these divisions get out into the streets and wreak havoc. Ironically, it's our Independence Day — a day when instead of celebrating our nation, it's all about “us” real Poles versus “them” real Poles, with xenophobia, violence, flare guns, police and tear gas involved. It's days like these that make me think of stereotypes, social identity theory and a few cognitive biases that make us look at the world as an us vs. them world, completely lacking any will to understand and co-exist with “them.”

Social identity theory

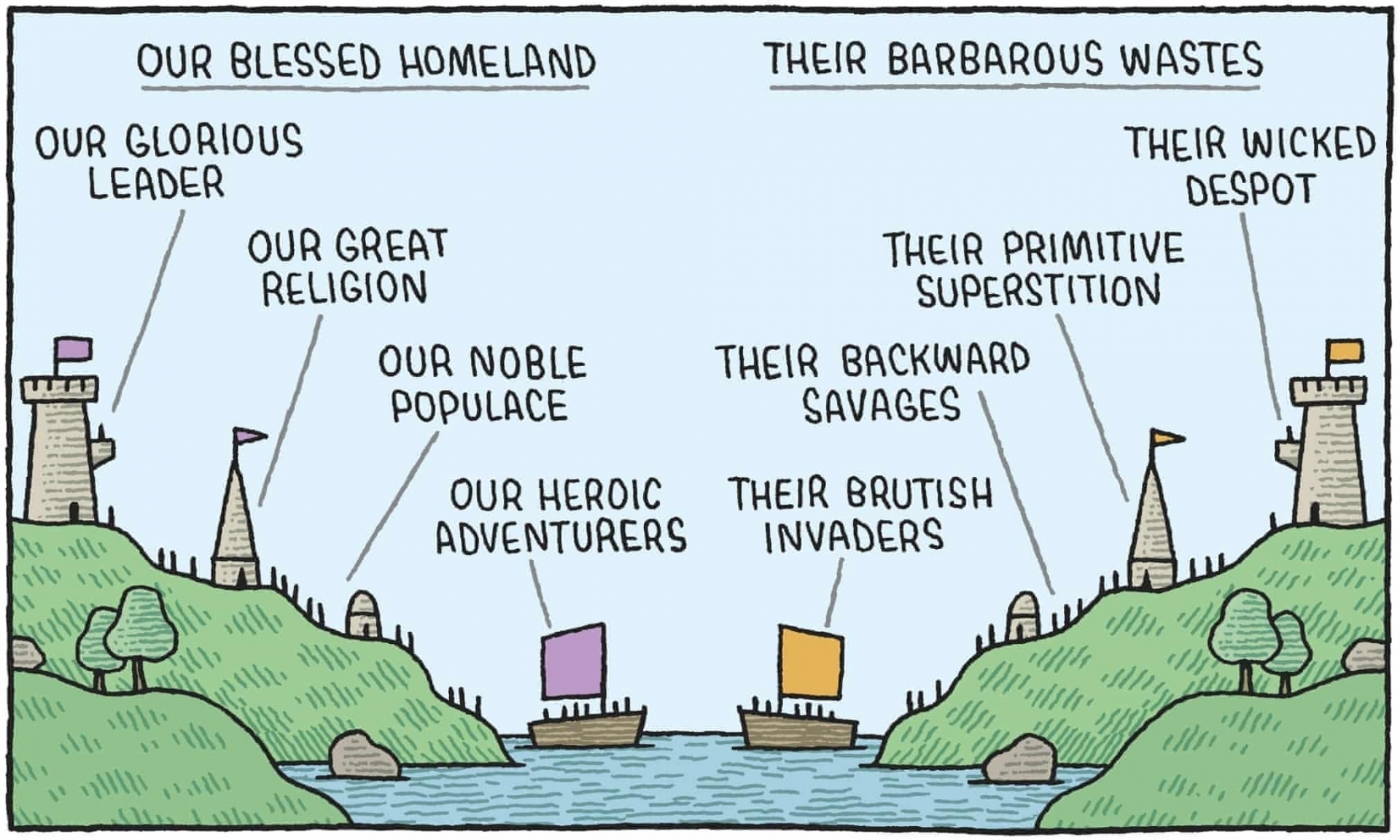

At the end of the 1970s, two psychologists, Henri Tajfel and John Turner, described this human tendency to divide ourselves into groups and to perceive our group(s) as better than others: We're good, they're bad.

Discrimination as a way to improve self-esteem

Unfortunately, appetite comes with eating, as they say, and feeling part of a group is often not enough. We tend to go a step further and start seeing our group(s) as better, discriminating out-group members — them. To improve our self-image, we boost the image of our group (Poland is the best country in the world!), and we start discriminating against other groups (Germans and Russians are stupid!).

According to Tajfel’s theory, this process has three stages:

Stage 1: Social categorization. We see the world as a collection of social groups, and we see people as members of these groups. Just note how we typically introduce ourselves to strangers: Hello, my name is Julia, and I’m from Poland. It's usually in the first sentence that we state our name and the country or city we come from.

Stage 2: Social identification. Because we see the world as a series of different social groups, we automatically identify with some of them and not identify with others.

Stage 3: Social comparison. We compare these social groups. If they're groups we belong to, we focus on the characteristics that unite us. If they're groups we don't belong to, we focus on the features that differentiate us. If someone from our group does something wrong, we tend to explain their behavior by external factors, i.e., situation (He didn’t help her, because he must have been in a hurry.). Yet, when an out-group member does the same thing, we tend to assign their behavior to internal factors (He is a heartless, bad person.).

Minimal group paradigm

Tajfel’s research showed just how strong this tendency of ours to see the world in terms of us vs. them is. We don’t have to share experiences, history, or values with others to start feeling like we're members of the same or opposing groups. Even people divided into groups based on insignificant features such as eye color, or random incidents such as a coin toss, immediately start displaying behaviors that favor their in-group members and start discriminating against out-group members.

Beat them > Have more

The same studies by Tajfel showed that we tend to maximize the relative position of our group in relation to an out-group, even if this means having objectively less. The participants in Tajfel’s studies preferred to receive less if it meant winning with the other group than to gain more but to allow the second group to have more as well.

Key Cognitive Biases

Bias #1: Outgroup homogeneity effect

Outgroup homogeneity effect is our tendency to perceive members of an out-group as more alike and more homogeneous than the members of one’s group.

In extreme situations, this can lead to Republicans in the United States thinking that all Mexicans are criminals because if one person from Mexico robbed a store once, it means that “they” all do it. All Syrian refugees must be terrorists and rapists because they are mostly young men, and once upon a time, somewhere, someone heard that a Syrian man raped a woman in Sweden. Besides, Syria is a Muslim country, and all Muslims are terrorists, right? And in Poland, all those who vote for PiS [the Law and Justice Party] must be uneducated idiots, and all those who vote for PO [the Civic Platform Party] are egocentric rich jerks.

(Dear Reader, please note the sarcasm in all these sentences!)

Bias #2: Stereotypes

The examples described above are, of course, examples of stereotypes that we all know so well. Stereotypes are nothing more than over-generalized beliefs about particular categories of people.

Seeing the world in terms of stereotypes is a natural human tendency and, contrary to popular belief, it is a much-needed mechanism (mental shortcut). It helps us to navigate the very complex world we live in, by not having to analyze as much information. We can simply label a person based on first appearances, instead of having to spend time and mental resources learning about who they are. We don't have to try to figure out if they're friends or out to get us. Problems arise when we are unaware that such stereotypes are just mental shortcuts — a type of a cogtnive bias — and start overdoing it.

Biases #3 and #4: Selective perception and confirmation bias

Selective perception and confirmation bias are the last two nails in the coffin.

Selective perception is our tendency to overlook and forget information that contradicts our beliefs. As a result, even if we see a positive behavior displayed by an out-group member, we don't pay attention to it. Instead, we push this incident out of our minds or otherwise rationalize it, for example, by dismissing it as an exceptional situation, so that it loses importance.

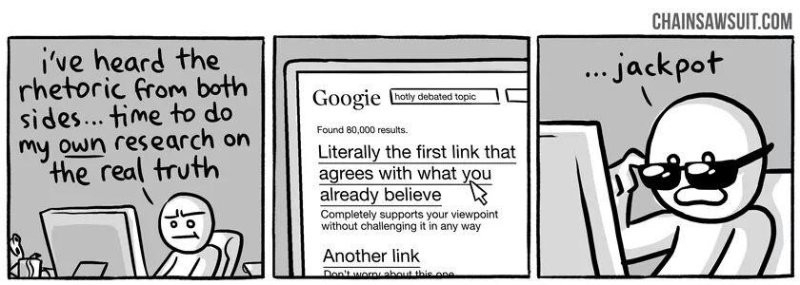

Confirmation bias is our tendency to prefer information that confirms our expectations and existing beliefs, regardless of whether the information is true or not. It leads us to search for information in sources that confirm our opinions.

Coded by evolution in the deepest layers of our brains

The world we live in has changed dramatically. Yet, our brains have not kept up with this change. We're still wired as we were hundreds of thousands of years ago. Our brains still have to balance the workings of two primary systems – the amygdala and mesolimbic system. Amygdala is responsible for generating a sense of fear and mistrust towards things and people that may pose a threat to our survival. The mesolimbic system is responsible for the feeling of pleasure when we do things that increase our chance of survival.

And what increases our chances of survival? People from our group! What poses a threat to our lives? Strangers! That is why, when we interact with people we don’t know, our amygdala tells us it is better to be afraid of them and to keep a safe distance. In response, our minds do everything they can to slander the out-groupers, to make them unattractive and anonymous. It makes them them.

Likewise, being part of a group is an evolutionary survival mechanism. Our mesolimbic system tells us that our people are good. In response, our minds do what they need to do — they see in-groupers in the best light possible, they make us enjoy being with them and not see their shortcomings.